How hard it is to build a realtime multiplayer browser game? Like asteroids, but multiplayer. Retro vibes with modern netcode 🚀.

Realtime multiplayer in the browser

Until relatively recently, realtime multiplayer in the browser was hamstrung by the lack of an unreliable network transport. Everything the browser did was TCP, and the realtime option was websockets.

TCP has head-of-line blocking though, because it’s a reliable ordered stream. If you’re streaming positional updates 60 times a second, and one of those packets is dropped or delayed, TCP won’t deliver any newly arrived packets to your game until the dropped one is retransmitted, effectively delaying all subsequent packets too. That’s why realtime netcode prefers UDP.

With UDP it’s up to your game protocol to handle dropped packets, which is extra work, but means you can stream realtime data and not suffer the same issues as TCP. Packets are delivered to your game as soon as they arrive, regardless of any packet loss or delays.

If only there was a way to do this in the browser..

Browser technologies for unreliable datagrams

WebRTC, which is designed for video and audio calling in the browser, has an Unreliable Datachannel option (UDP). This is suitable, but there is quite a lot of machinery required to present yourself as a WebRTC server just to open a data channel.

The newish WebTransport API operates over HTTP/3, using QUIC – atop UDP. It supports unreliable data channels, and is less of a headache to use serverside. Nowadays this seems like a decent choice for the in-browser network layer for a realtime game.

Choosing a network model, abridged

To figure out how to network multiplayer asteroids, it behooves us to consider one of the most common approaches to netcode called Snapshot Interpolation – used by first person shooters for decades.

Quake, et al.

Quake, and many FPS games that came after it, can be described as:

A bunch of players moving around a mostly static world, shooting at each other.

These games are continually sending your inputs (move forward, jump, shoot..) to the server. The server is simulating your character, along with the rest of the players, as inputs arrive. The server streams snapshots back to you containing up-to-date positions at specific points in time (each “tick”).

To smooth out the movement, the game buffers incoming snapshots and interpolates between two recent ones to compute player positions. This gives silky smooth movement, but results in you seeing a slightly outdated position for other players.

This is the standard approach for competetive FPS. You can tune the buffers to smooth over network lag spikes, at the cost of moving remote player timelines further into the past.

Local-player Prediction and Rollback

To further complicate matters, when you hit W to move forward, the game doesn’t wait for a server update before moving your own player’s position. Your own position is predicted, not interpolated, ie. when you press forward, your local player immediately moves forward, while your I'm pressing W on tick 123 packet travels to the server. The server processes it, dutifully moves your player forward, and includes the new position in the next snapshot.

Your game client, which kept a record of your predicted movement and inputs for the last few ticks, will need to reconcile this with updates received from the server. If the snapshot position at a given tick matches the position in your buffer at that tick, that’s ideal. If there was a misprediction, you wind back your position to the tick from the snapshot, snap your player to the snapshot-position, and replay any stored input commands to fast-forward your predicted location back to your current predicted tick on the client.

Snapshot interpolation asteroids?

What happens if we apply this model to multiplayer asteroids? We predict movement of your own ship, just like FPS, and do snapshot interpolation for remote players and asteroids.

The movement of players and asteroids would be nice and smooth, right up to the moment you collide with something.

Your ship is locally predicted ahead of the server, based on your inputs. Remote asteroids or players are shown in the past, due to snapshot interpolation. So you’re essentially seeing the position of other objects but from (say) 75ms in the past.

For a game that would surely involve lots of crashing into other players and asteroids, we don’t want janky collisions.

Client Prediction & Rollback for Everything

Asteroids are pretty simple, they just keep moving until they collide with something. So we’ll have our client project their position forward into the same timeline as the local player. This means we run same physics simulation code on the client as we do on the server.

We’ll store a historical record for each entity: the last few frames of position/rotation. When we get a server update about a position, we can check it against our historical record for that tick. If there were any discrepencies, we perform a rollback: wind back time to the tick from the server update, snap positions to the server-authoritative position, and fast-forward back to our current tick, resimulating the physics as we go – and in the case of mispredicted players, re-applying any stored inputs.

Any errors corrected after rollback, as a result of a misprediction, can be blended in visually over a few frames. Meanwhile the underlying state of the client’s physics always strives to be as correct as possible.

Experiments with Bevy

I did some experiments with the bevy game engine and a home-grown netcode/rollback system to explore what would work for multiplayer asteroids.

Client-prediction, single player

This experiment, with just one player connected to the server, predicts the position of asteroids into the same timeframe as the player. The grey outlines show the most recent position of the object received from the server. The server tick rate is set fairly low so it’s easy to see what’s happening. There were no mispredictions, because with just one player connected, everything is deterministic.

If you fullscreen this video, you’ll be able to see the light grey outline of each entity - that is the last received authoritative server position. The colored outlines are where the client has predicted them in the client timeline. No rollbacks or jank because with a single player, there aren’t any mispredictions.

Timeline jank experiment

Here’s an experiment I conducted testing how collisions behave differently when asteroids are predicted forward into the same timeline as the local player.

Movement looks good in isolation, however per my voiceover in the next video, remote players do get janky collisions. This is because of the temporal disrepency between remote players and other objects. With remote players held 6 frames in the past, which equates to around 100ms, there are janky collisions. Watch what happens to collisions when I enable input prediction for remote players, to bring them into the same timeframe as the local player and asteroids:

Predicting Remote Players

Since we don’t have up-to-date inputs for remote players on our most recent ticks, we just assume they are still pressing the same buttons as the last-known input. Players holding down forward are most likely to still be holding down forward.

This, plus smearing errors due to mispredictions over a couple of frames, can work pretty well, provided we keep player latency to a reasonable amount.

We can also bake in 3 ticks of input delay for all players. So inputs a client presses are used for t+3, but sent to the server immediately and rebroadcast to other players. This means sometimes you do in fact have all inputs for remote players, or at least only have to guess 1 or 2 ticks worth.

Implementation Details

These experiments really helped me understand what kind of netcode model I needed – but I ended up throwing away most of the code I’d written. My rollback implementation was kind of a mess, being very new to rust, bevy, and gamedev in general. I was very happy to discover Lightyear, which has built-in prediction & rollback, and WebTransport support that works on native and WASM builds.

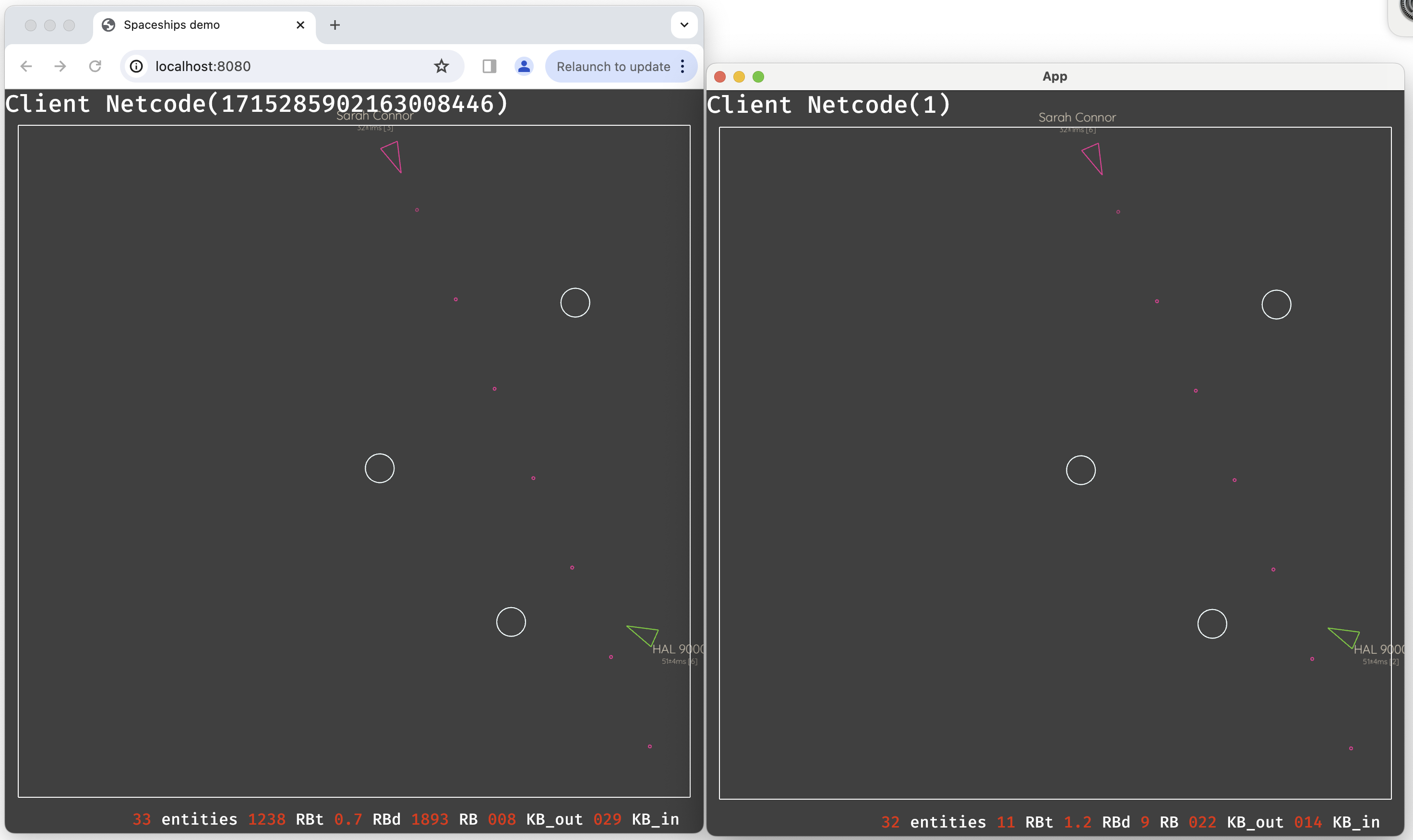

I contributed a basic asteroid-esque game to the Lightyear examples, called spaceships, which allowed me to experiment with how things like predicted bullet spawning should work. The spaceships demo does client prediction for players and “asteroids” (well, circles). It compiles to wasm and works in Chrome (as of this post, I think it works in firefox nightly but not stable yet):

Onwards

Time to build a game! But wait, let’s procrastinate a little more first by trying to figure out a good way to deploy multiplayer bevy games that use lightyear..

Links

- It IS Rocket Science! The Physics of Rocket League Detailed a great GDC talk. Rocket League uses a similar network model.

- Choosing the right network model for your multiplayer game by Glenn Fiedler. All his articles about game networking are essential reading.

- Bevy - A refreshingly simple data-driven game engine built in Rust

- Lightyear - A fantastic networking library to make multiplayer games for the Bevy game engine

See my other posts tagged as ‘bevygap’.